CORRECTED: with an aircraft wing, the lifting force does not come

from the difference in curvature between the top and bottom surfaces.

First read the entire: wings/lift webpage

Some books say that the lifting force appears

because the wing's upper surface is longer than the

lower surface.

They state that air dividing at the leading edge of the wing must rejoin

at the trailing edge, therefore the upper air stream must move faster, and

so the wing is pulled upwards by the Bernoulli Effect. This is not

correct: the air divided by the leading edge

does NOT rejoin at the

trailing edge, and there is no "race" to catch up.

The same books often

contain a misleading diagram showing a

flat-bottomed wing with flow lines of the surrounding air. (see below.)

This diagram actually shows a zero-lift condition. The lifting force is

zero because the air behind the airfoil does not descend. In order to

create

lift in a three-dimensional situation, a wing must deflect air

downwards.

Both the explanation and the diagram have serious problems. They wrongly

imply that inverted flight is impossible. They wrongly imply that an

aircraft with a symmetrical wing (a wing with equal

pathlengths above and below) will not fly. They also

wrongly suggest that an aircraft can violate the conservation of momentum

by remaining aloft without reacting against the air, and without causing a

downward motion of the air.

Yet upside-down flight is far from

impossible; it is a common aerobatic move. And many wings have equal

pathlengths, including even the thin cloth wings of the Wright Brothers'

flyer! And anyone standing under a slow, low-flying plane, or below the

thin, fast wings of a helicopter will know that there is a very great

downward flow of air below the wings. All of this indicates that there is

a serious problem with the "curved top, flat bottom" explanation. Below

is an alternative.

Go listen to NPR Science Friday Radio Archive, where physicist D. Anderson

debunks the various lifting-force myths.

Also see the NASA Aerodynamics Education site:

Here's my attempt at a correct explanation:

As a plane flies, the leading edges of its wings have little effect on

the

air, while the

trailing edges have a huge effect.

The wings' trailing edges always move through the air at an angle.

This "effective angle

of attack" causes the wing to apply a downward force to the air.

In order to create lift, the wing must be tilted. Or

rather than being tilted, the wings can be curved or "cambered",

which makes the trailing edge of the wing tilt downward at an angle.

The trailing edges of the wings cause the departing air to move downwards at an angle. As a

result, the wing is pushed

upwards and backwards. (These two pushes are called "lift" and "induced

drag.")

The tilted lower surface of the wing causes air to move down, but that's

not the only thing. The TOP of the wing also guides the

flowing air. This is called "flow attachment" or "Coanda Effect."

As the wing moves forward, the air ABOVE the wing moves down, and the

wing is forced upwards.

In other words, as any plane flies, its wings must send a stream of air

diagonally

downwards, and the wing acts like a 'reaction engine' just

like a jet engine or a rocket. Unless a wing is either tilted or

cambered, it cannot force the air downwards and cannot generate any

"lift."

It may help to imagine a hovering

helicopter: a helicopter can hover because its rotor applies a downward

force to the air, and the air applies an upward force to the rotor. As a

result, the air flows downwards while the upward force supports the

craft.

But like any airplane, a helicopter rotor is a moving wing, and it's this

small tilted wing which

sends the air downwards. Like any wing, helicopter rotors are reaction

engines, they

push air downwards, and the air pushes them upwards. They are not "sucked

upwards," and neither are airplanes.

You may have seen a plane's downwash of air in movies: a "cropduster"

plane sends out a trail of fertilizer mist, and the trail of mist does not

float, instead it moves immediately down into the crops, driven downward

by the moving air. Air from wings can even be dangerous: if a plane flies

too low, the downwash from its wings can knock people over.

The "Bernoulli effect" is still true. It explains how the top of the

wing is able to "pull downwards" on

the air flowing over it. And the Bernoulli Effect proves extremely useful

in calculations

of the lifting force during classes in airplane physics and during

experimental work in aerodynamics. But airplanes also obey Newton's

laws: accelerate some air downwards, and you'll experience an upwards

force.

Sound travels better through solids? No.

Many elementary textbooks say that sound travels better through solids and

liquids than through air, but they are incorrect. In fact, air, solids,

and liquids

are nearly transparent to sound waves. Some authors use an experiment to

convince us differently: place a solid ruler so it touches both a ticking

watch and your ear, and the sound becomes louder. Doesn't this prove that

wood is better than air at conducting sound? Not really, because sound

has an interesting property not usually mentioned in the books:

waves of sound traveling inside a solid will bounce off the air outside

the solid.

The experiment with the ruler merely proves that a wooden rod can act as a

sort of "tube," and it will guide sounds to your head which would

otherwise spread in all directions in the air. A hollow pipe can also be

used to guide the ticking sounds to your head, thus illustrating that air

is a good conductor after all. Sound in a solid has difficulty getting

past a crack in the solid, just as sound in the air has difficulty getting

past a wall. Solids, liquids, and air are nearly equal as sound

conductors.

It's true that the speed of sound differs in each material,

but this does not affect how well they conduct. "Faster" doesn't mean

"better." It is true that their transparency is not exactly the same, but

this only is important when sound travels a relatively great distance

through each material. It's also true that complex combinations of

materials conduct sound differently and may act as sound absorbers

(examples: water with clouds of bubbles, mixtures of various solids, air

filled with rain or snow.) And last: when you strike one object with

another, the

sound created inside the solid object is louder than the sound created in

the surrounding air. So, before we try to prove that solids are better

conductors, we had better make sure that we aren't accidentally putting

louder sound into the solids in the first place.

Gravity in space is zero? Wrong.

Everyone knows that the gravity in outer space is zero. Everyone is

wrong. Gravity in space is not zero, it can actually be fairly strong.

Suppose you climbed to the top of a ladder that's about 300 miles tall.

You would be up in the vacuum of space, but you would not be weightless at

all. You'd only weigh about fifteen percent less than you do on the

ground. While 300 miles out in space, a 115lb person would weigh about

100lb. Yet a spacecraft can orbit 'weightlessly' at the height of your

ladder! While you're up there, you might see the Space Shuttle zip right

by you. The people inside it would seem as weightless as always. Yet on

your tall ladder, you'd feel nearly normal weight. What's going on?

The reason that the shuttle astronauts act weightless is that

they're inside a container which is falling! If the shuttle were to

sit unmoving on top of your ladder (it's a strong ladder,) the shuttle

would no longer be falling, and its occupants would feel nearly normal

weight. And if you were to leap from your ladder, you would feel just as

weightless as an astronaut (at least you'd feel weightless until you hit

the ground!)

So, if the orbiting shuttle is really falling, why doesn't it hit

the earth? It's because the shuttle is not only falling down, it is

moving very fast sideways as it falls, so it falls in a curve. It moves

so fast that the curved path of its fall is the same as the curve of the

earth, so the Shuttle falls and falls and never comes down. Gravity

strongly affects the astronauts in a spacecraft: the Earth is strongly

pulling on them so they fall towards it. But they are moving sideways so

fast that they continually miss the Earth. This process is called

"orbiting," and the proper word for the seeming lack of gravity is called

"Free Fall." You shouldn't say that astronauts are "weightless," because

if you do, then anyone and anything that is falling would also be

"weightless." When you jump out of an airplane, do you become weightless?

And if you drop a book, does gravity stop affecting it; should you say it

becomes weightless? If so, then why does it fall? If "weight" is the

force which pulls objects towards the Earth, then this force is still

there even when objects fall.

So, to experience genuine free fall just like the

astronauts, simply jump into the air! Better yet, jump off a diving board

at the pool, or bounce on a trampoline, or go skydiving. Bungee-jumpers

know what the astronauts experience.

Space isn't remote at all. It's only an hour's drive away if your car

could go straight upwards. --Fred Hoyle

CORRECTED: For every action, there is not an

equal and opposite reaction.

Newton originally published his laws of motion in Latin, and in the

English translation, the word "action" was used in a different way than

it's usually used today. It was not used to suggest motion. Instead it

was used to mean "an acting upon." It was used in much the same way that

the word "force" is used today. What Newton's third law of motion means

is this:

For every "acting upon", there must be an equal

"acting upon" in the opposite direction.

Or in modern terms...

For every FORCE applied, there must be an equal FORCE

in the opposite direction.

So while

it's true that a skateboard does fly backwards when the rider steps off

it, these motions of "action" and "reaction" are not what

Newton

was investigating. Newton was actually referring to the fact that when

you push on something, it pushes back upon you equally, even if it

does not move. When a bowling ball pushes down on the Earth, the

Earth pushes up

on the bowling ball by the same amount. That is a good illustration of

Newton's third Law. Newton's Third Law can be

rewritten to say:

For every force there is an equal and opposite force.

Or "you cannot touch without being touched."

Or even

simpler: Forces always exist in pairs.

CORRECTED: Ben Franklin's kite was never struck by

lightning

Many people believe that Ben Franklin's kite was hit by a lightning

bolt, and this is how he proved that lightning is electrical. A number

of books and even some encyclopedias say the same thing. They are wrong.

When lightning strikes a kite, the electric current in the string is so

high that just the spreading electric currents in the ground can kill

anyone standing nearby, to say nothing of the person holding the string!

What Franklin actually did was to show that a kite would collect a tiny

bit of electrical charge-imbalance out of the sky during a thunderstorm.

Air is not a perfect insulator. The charges in a thunderstorm are

constantly leaking downwards through the air and into the ground.

Electric leakage through the air caused Franklin's kite and string to

become charged, and the hairs on the twine stood outwards. The twine was

then used to charge a metal key, and tiny sparks could then be drawn from

the key. Those tiny sparks were the only "lightning" in his experiment.

(He used a metal object because sparks cannot be directly drawn from

the twine; it's conductive, but not conductive enough to make sparks.)

His experiment told Franklin that some stormclouds carry strong electrical

charges, and it implied that lightning was just a large electric

spark.

The common belief that Franklin easily

survived a lightning strike is not just wrong, it is dangerous: it may

convince kids that it's OK to duplicate the kite experiment as long as

they "protect" themselves by holding a silk ribbon and employing a metal

key. Make no mistake, Franklin's experiment was extremely dangerous.

Lightning goes through miles of insulating air, and will not be stopped by

a piece of ribbon. If lightning had actually hit his kite, he would have

been gravely injured, and most

probably would have died instantly. See LIGHTNING SURVIVOR RESOURCES

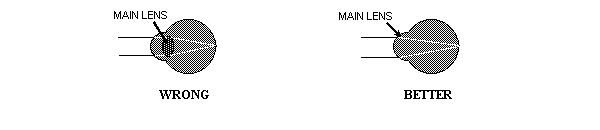

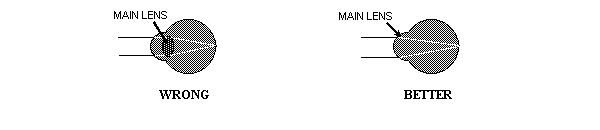

The main lens of your eye is inside the eye? Not quite.

Some textbooks assume that the small lens found deep within the eyeball is the

eye's main lens, and the cornea of the eye is simply a protective window.

The textbook diagrams even depict light rays passing into the eye and only

bending as they pass through this internal lens. But in the human eye,

the small lens found within the eyeball is not the main imaging lens. The

cornea is actually the main lens; it is the strongly curved transparent

front surface of the eye. Most of the bending of the light occurs at the

place where the light enters the surface of the cornea. When you look at

your eye in the mirror, you are looking directly at the eye's main lens.

When you want to change the focusing power of your eye, you apply

"contact lenses" to the cornea surface, or you undergo surgery which

re-sculpts the cornea's curvature. The smaller lens inside the eye acts

only to alter the focus of the eye as a whole. Muscles change its shape

in order to correct the focus for near and far viewing. Without this

small internal lens, human vision would be blurry, and vision

would be

unable to accommodate for near and far views. But without the cornea lens,

[the human eye would be blind.] IMPROVED VERSION: without the

cornea

lens, human

vision would rely upon the pinhole-camera effect of the eye's pupil,

and vision would be incredibly blurry. Open your eyes underwater in

dimly-lit conditions to see what vision would be like without a cornea.

|

CORRECTED: when one prism splits light into colors, a

second identical prism cannot recombine them.

A single prism can split a sunbeam into a rainbow. Many children's

science books show how a second similar prism can be used to recombine the

colors. This is incorrect, two prisms do not work as shown. Prisms of two

different sizes can split and then focus the colors into momentary

recombination at a particular distance. With three prisms in a

special arrangement, the splitting and complete recombining of colors can

be accomplished. But books which depict one prism splitting the colors

and a second identical prism recombining the colors into a single white

beam are in error, and are no doubt the source of endless frustration for

those of us who try to duplicate the effect with real prisms.

The "rainbows" can also be recombined by placing a screen at just

the right place, and by bouncing the colors off many small mirrors so the

colored beams converge upon a screen. Recombination can also be done with

a convex lens or a concave mirror and a screen. I hope that very few

students will attempt to perform the color recombination experiment

depicted in their books, for disappointment awaits. (MORE)

Clouds, fog, and shower-room mist are water vapor? No.

All three things are made of small droplets of liquid water hanging in

the air. When water

evaporates,

it turns into a transparent gas called "water vapor." When it condenses

again, it can take the form of rain, snow, rivers, and oceans, but it also

can take the

form of clouds, mist, fog, etc. Fog can make surfaces wet, but not

because of condensation. Instead, the fog droplets collide with the

solid surface. Fog is liquid water, not a vapor. Fly an ultralight

aircraft

slowly through a large dense cloud, and you'll become damp. To look for

water vapor, look at the bubbles in rapidly boiling water. Look at the

small empty space at the spout of a boiling teakettle. Look at the far

end of the teakettle's plume of mist, where the mist seems to vanish into

the air. Look at the empty air above a wet surface. In these situations

you see nothing, and that's where the vapor is. Water vapor seems

invisible because it is transparent. Clouds and fog are not transparent.

They are composed of liquid droplets.

CORRECTED: raindrops don't have points!!

Nearly every

drawing of raindrops depicts them as having a sharp upper point. This is

wrong. Surface tension of water acts like a stretched "bag" around the

water, and unless some other force is acting, it pulls the water into a

spherical shape. Our eyes do see tiny droplets as a blur, but a flash

photograph reveals that small raindrops are nearly spherical. The larger

ones are distorted by the pressure of moving air, but this doesn't make

points, it makes them somewhat flattened. Think of it this way:

underwater bubbles are not pointed as they rise, just as falling water

drops are not pointed as they fall. And while it's true that the

symbol

for water is a droplet with a point, real water droplets look

nothing like

the symbol. And when water drips from a faucet, it never actually has a

point. Instead it has a narrow neck, and after the neck has snapped, it

is yanked back into the falling ball of water. See Dr. Fraser's BAD SCIENCE for

lots more about this.

Air is weightless? No.

We are not conscious of

air's weight because we are immersed within it. In the same way, even a

large bag of water seems weightless when it is immersed in a water tank.

The bag of water in the tank is

supported by buoyancy. In a similar way,

buoyancy from the atmosphere makes a bag of air seem weightless when it's

surrounded by air. One way to discover the real weight of air would be to

take a bag of air into a vacuum chamber. Another way is to weigh a

pressurized and an unpressurized football. A cubic meter of air at

sea-level pressure and

0C temperature has a mass of 1.2KG. The non-metric rule of thumb says

that the air that would fill a bathtub weighs about one pound.

Here's a simple way to

detect

the mass of air even though the air seems weightless: open an umbrella,

wiggle it slightly forwards and back, then close it and wiggle it again.

When you wiggle it when open, you can feel its increased mass because of

the air the umbrella must carry with it. (Ah, but then we must explain

the difference between weight and mass!)

CORRECTED: Filled and empty balloons do not demonstrate

the weight of air.

Many books contain an incorrect experiment which purports to directly

demonstrate that air has weight. A crude beam-balance is constructed

using a meter stick. Deflated rubber balloons are attached to the ends,

and the balance is adjusted. One balloon is then inflated, and that end

of the balance-beam is supposed to sag downwards. The demonstrator then

explains that a large amount of air weighs more than a small amount of

air.

Unfortunately this experiment isn't very honest. When immersed in

atmosphere, buoyancy

causes full and empty balloons to weigh the same. One balloon shouldn't

pull down the stick. But then why does the

above experiment work? Usually it doesn't! In fact, the experiment will

fail unless you know the trick: you must inflate the balloon near to

bursting. The experiment secretly relies on the fact that the air within

a high-pressure balloon is denser than air within a low pressure balloon.

Of course the demonstrator never mentions this to the students, and the

books which contain this demonstration don't mention density effects

either. Obviously the density effects do not directly demonstration

anything about the weight of air, so it's dishonest to tell students that

this demonstration can directly weigh some air.

To illustrate the problem, try this instead: attach two opened paper bags

to the balance, adjust it, then crush one bag so it contains little air.

The balance will not change. What does this teach your class; that

air is... weightless? Yet the air does have significant weight. We just

can't detect this weight directly by using paper bags. Or using

balloons.

Here's a way to make the experiment more honest. Perform the balance-beam

experiment again, but use two full balloons. Blow one balloon

really full so the rubber feels hard and the balloon is about to

pop. Blow up the second balloon so it is almost full, but still a

bit

stretchy. Try to keep the balloons almost the same size. Now the balance

will show that, even though the balloons look nearly the same, the "hard"

balloon is significantly heavier. Does this teach misleading things to

your class? Not really, instead it exposes the dishonesty of the original

demonstration. In truth, balloons filled with air will not weigh more

than empty balloons as long as they remain immersed in the atmosphere.

However, compressed air does weigh more than uncompressed

air. Perhaps this modified demonstration would be appropriate in more

advanced classes. But this website is about K-6 grade science.

Here's another way to think about it. Can we demonstrate the weight of

water to a fish?

What if we lived underwater, how could we use the balance-beam to measure

the weight of water directly? The answer is that we cannot. If a

water-filled balloon and a collapsed empty balloon were compared

underwater,

the experiment would show that they weigh the same, which seems to prove

that water is weightless. When underwater, a bag full of water weighs

just the same as a flattened bag which contains nothing. The situation

with air is similar: if we live our lives immersed within a sea of air,

we cannot use a balance to easily detect the actual weight of the air. (In

fact, a bathtub full of air weighs about a half kilogram, but we cannot

easily demonstrate this weight while living in an atmosphere.)

It's hard to teach the weight of water to the fishes, and hard to teach

the weight of air to human grade-schoolers. These misleading textbook

experiments could only work correctly if performed in a vacuum environment

(say, on the moon's surface.) We humans are like fish underwater: we're

not aware that our ocean of air has any weight. To demonstrate the

weight, we need to get out into a vacuum environment.

Or, to better demonstrate the weight of air directly, hook a heavy bottle

to a

vacuum pump, pump all the air out, seal it, then weigh the bottle. Break

the seal and let the air in, then weigh it again. The difference in

weight is the weight of the air contained in the bottle. Another: use a

balance to compare the weight of two vacuum-containing bottles, then open

one of them so it becomes filled with air. The bottles will then weigh

differently, and the difference is the true weight of the air in one

bottle. Or another: build a balance using upside-down paper bags, then

place a candle below one of them, then remove the candle again. That bag

rises, indicating that a volume of warm air weighs slightly less than a

volume of cool air. (Don't set the bag on fire!!) But note that this

candle experiment is a bit like the compressed balloon version, and it

says nothing simple and direct about the actual weight

of a volume of unheated air.

CORRECTED: in the everyday world, gases do not expand to

fill their containers.

What is the difference between a liquid and a gas? Both are "fluids",

both can flow. Gases are usually less dense than liquids, although

gases under fiercely high pressure can approach the density of liquids, so

that's not a good criterion. The main difference is that gases are a

different phase of matter: a gas can be made to condense into a liquid

form, and a liquid can be made to evaporate into gas. Another major

characteristic: because there are bonds between its particles, when a

liquid is placed into a vacuum environment, it will not immediately

and continuously expand, while a gas in a vacuum chamber will expand at

high velocity until it hits the container walls.

This is very different from the oft-quoted rule that "gases always expand

to fill their containers." This rule only works correctly if the

container is totally empty: the container must "contain" a good

vacuum beforehand. However, we all live in a gas-filled environment. All

our containers are pre-filled with air. In our environment, any new

quantity of gas will not expand, it will just sit there. It may slowly

diffuse outwards, but that's very different than the "expansion" being

discussed here. If

you squirt

some carbon dioxide out of a CO2 fire extinguisher, it will not instantly

expand to fill the room. Instead it will pour downwards like an invisible

fluid and form a pool on the

floor. It behaves similarly to dense sugar-water which was injected into

a tank of water: it pours downwards, and only after a very long time it

will mix with the rest of the water. "Mixing" is very different from

"expanding to fill!" The rule about gases does not involve mixing;

instead it involves compressibility and instant expansion into a vacuum.

In an air-filled room, dense gases act much like liquids; they can be

poured into a cup or bowl, poured out onto a tabletop, and then they

run off the edge onto the floor where they form an invisible mess. :)

Less dense gases will stay where they are put, like smoke or like food

coloring which has just been injected into a fishtank. Gas of even lesser

density rises and forms a pool on the ceiling. Only in the world

of the physicist, where "empty container" always implies a vacuum, does

the rule about gasses work properly.

CORRECTED: Shadows do vanish on cloudy days, but not

because the sun isn't bright enough.

Shadows appear when an object blocks a light source. The shape of the

shadow is created by the shape of the opaque object and by the

shape of the light source. On a cloudy day the whole sky acts as a light

source, and a person's shadow spreads out and becomes a dim fuzzy patch

which surrounds the person on the ground on all sides. The shadow is so

spread-out that it seems absent entirely. When the sun is visible, the

same shadow is concentrated in one specific place and becomes easy to see.

But even the shadows made by sunlight will have fuzzy borders, since the

sun is a small disk rather than a tiny dot. On cloudy days, the fuzzy

borders of your body's shadow become much much larger than the shadow

itself, so that the shadow seems to vanish.

CORRECTED: FRICTION IS NOT CAUSED BY SURFACE ROUGHNESS

Some books point to surface roughness as the explanation of sliding

friction. Surface roughness merely makes the moving surfaces bounce up

and down as they move, and any energy lost in pushing the surfaces apart

is regained when they fall together again. Friction is mostly caused by

chemical bonding between the moving surfaces; it is caused by stickiness.

Even scientists once believed this misconception, and they explained

friction as being caused by "interlocking asperites", the "asperites"

being microscopic bumps on surfaces. But the modern sciences of surfaces,

of abrasion, and of lubrication explain sliding friction in terms of

chemical bonding and "stick & slip" processes. The subject is still full

of unknowns, and new discoveries await those who make surface science

their profession

When thinking about friction, don't think about grains of sand on

sandpaper. Instead think about sticky adhesive tape being dragged along a

surface.

CORRECTED: NO, INFRARED LIGHT IS NOT A KIND OF HEAT

Infrared light is invisible light.

When any type of light is absorbed by an object, that object will be

heated. The infrared light from an electric heater feels hot for two

reasons: because surfaces seem black to IR light, and because the IR is

extremely bright light. Just because human eyes cannot see the

light which

causes the heating does not mean it's made of some mysterious entity

called "heat radiation." When bright light shines on an absorptive

surface, that surface heats up.

And this is no benign misconception. Those who fall under its sway may

also come to believe that *visible* light cannot heat surfaces (after all,

visible light is not "heat radiation?") Misguided science students may

wrongly believe that warm objects emit no microwaves (since only IR light

is "heat radiation"), even though hot objects actually do emit microwaves.

Or students may believe that the glow of red hot objects is somehow

different from the infrared glow of cooler objects. Or they may believe

that IR light is a form of "heat," and is therefore fundamentally

different from any other type of electromagnetic radiation.

In his book "

Clouds in a Glass of Beer," Physicist C. Bohren points out that this

"heat" misconception may have been started long ago, when early physicists

believed in the existence of three separate types of radiation: heat

radiation, light, and actinic radiation. Eventually they discovered that

all three were actually the same stuff: light. "Heat radiation" and

"actinic radiation" are simply invisible light of various frequencies.

Today we say "UV light" rather than "actinic radiation." Yet the obsolete

term "heat radiation" still lingers. Since human beings can only see

certain frequencies of light, it's easy to see how this sort of confusion

got started. Invisible light seems bizarre and mysterious when compared

to visible light. But "invisibility" is caused by the human eye, and is

not a property carried by the light. If humans could see all the light in

the infrared spectrum, we would say things like this: "of course

the

electric heater makes things hot at a distance, it is intensely

bright,

and bright light can heat up any surface which absorbs it."

PS, if

you're interested in physical science misconceptions,

Bohren's Book is an excellent resource. He's like me, and complains

about several specific misconceptions which keep his students from

understanding science.

CORRECTED: THERE ARE NOT SEVEN COLORS IN THE RAINBOW

Actually there's a very large number of distinct colors in any rainbow.

And neither are there sharp divisions between the bands of color, yet

numerous textbooks depict them. In reality, between yellow and green we

find yellow-green, and between green and yellowgreen is greenish

yellowgreen, and on and on. How many colors are in a rainbow? Thirty?

Sixty? It's not easy to say, for it depends on the particular eye, and

the particular rainbow. What of the teachers and students who look in

vain for the yellow-green in their textbook's depiction of rainbows?

They've crashed into a long-running textbook misconception: the strange

idea that rainbows have exactly seven distinct bands of color and no more,

and with nothing in between those uniform bands of 'official' color.

CORRECTED: ACTUALLY, THE EARTH'S NORTH AND SOUTH

MAGNETIC POLES RESIDE DEEP WITHIN THE EARTH'S CORE

Many textbooks have an erroneous diagram of the earth which shows

a bar magnet within it, and the ends of this bar magnet extend to just

beneath the earth's surface. These diagrams depict the magnet's field

lines as radiating from spots on the earth's surface. This is very

misleading. The earth's magnetic poles actually behave as if they're deep

within the earth, down inside the core. The Earth's magnetic field does

not come from a giant bar magnet, but if we imagine that it does,

then the imaginary "bar magnet" inside the earth is short, stubby,

disk-shaped, and part of the iron core deep inside the planet.

The typical textbook diagram is incorrect, and there are no intense

magnetic fields at the land surface near the earth's "north pole" and

"south pole." If you stand at the Earth's south magnetic pole, metals

aren't attracted to the ground more strongly than anywhere else. The

Geomagnetic "poles" on the earth's surface are not places where the field

is strong. They are simply the points on the landscape where the field

lines are perfectly vertical.

Proper diagrams

should instead show the field lines to be radiating from poles inside the

earth's core. They should show the field lines around the northern and

southern areas of the earth's surface as being approximately vertical and

parallel, not "radial" like a spiderweb and not concentrated into special

points on the surface.

Another error associated with the above: some books claim that the

earth's field at the magnetic poles is much stronger than elsewhere.

This is untrue. The field strength at the north magnetic pole above

Canada is about the same as the field strength in Virginia! And the

strongest field in the Earth's northern hemisphere does not appear at the

north magnetic pole at all, the North Pole actually has a weaker field

than elsewhere. The strongest fields in the northern hemisphere are not

in one but in two places: west of Hudson Bay in Canada, and in Siberia.

LINKS

LASER LIGHT IS "IN PHASE" LIGHT?

WRONG.

It's incorrect to say that "in laser light the waves are all in phase."

When two light waves traveling in the same direction combine, they

inextricably add together, they do not travel as two independent

"in-phase" waves. The photons in laser light are in phase, but the WAVES

are not. Instead, ideal laser light acts like a single, perfect wave.

When the light wave within a laser causes atoms to emit smaller, in

phase light waves, the result is not "in phase" light. Instead the result

is a single, more intense, amplified wave of light. In-phase emission

leads to amplification, not to multiple in-phase waves. If the atoms'

emissions weren't in phase, the result would not be light that's

out of phase. Instead the atoms would absorb light rather than amplifying

it.

Each atom in a laser contributes a tiny bit of light, but their light

vanishes into the main traveling wave. The light from each atom

strengthens the main beam, but loses its individuality in the process.

99 plus 1 equals 100, but if someone gives us 100, we cannot know if it is

made from 99 plus 1, or 98 plus 2, or 50 plus 50, etc.

Yes, it's true that all the photons associated with a single wave

of light are in phase. This might be one reason that people say that

laser light is "in phase" light. However, in-phase photons are nothing

unique, and they don't really explain coherence. Any EM sphere-wave or

plane-wave is made of in-phase photons. For example, all the photons

radiated from a radio broadcast antenna are also in phase, but we don't

say that these are special "in phase" radio waves, instead we just say

that they are waves with a spherical wavefront. Even if all the photons

in laser light are in phase, it is still incorrect to say "all the

WAVES are in phase." Photons are not waves. They are quanta, they

are particles, and they do not behave as small, individual "waves." Yes,

all the photons are in phase, but only because they are part of a single

plane-waves.

The light from a laser is basically a single, very powerful light wave.

Single waves are always in phase with themselves, but it's misleading to

imply that a single plane-wave or sphere-wave is something called an "in

phase" wave. Laser light could more accurately be called "pointsource"

light. Sphere waves or plane waves behave as if they were emitted from a

single tiny point. The physics term for this is "spatially coherent"

light. Light from light bulbs, flames, the sun, etc. are the opposite,

and are called "extended-source" light. Extended-source light comes from

a wide source, not from a point-source, and the waves coming from

different parts of the source will cross each other. Starlight and the

light from arc welders is "point-source" light and is quite similar to

laser light. Light from arc-welders and from distant stars has a higher

spatial coherence than light from most everyday light sources. (Note: the

sun is a star, correctly implying that light becomes more and more

spatially coherent as it moves far from its source. This is a clue as to

the real reason that lasers give spatially coherent light! (See

below)

CORRECTED: LASER LIGHT IS NOT PARALLEL LIGHT

Light from most lasers is not parallel light. However, if laser light is

passed through the correct lenses, it can be formed into a tight, parallel

beam. The same is not true for light from an ordinary light bulb. If

light from a light bulb were passed through the same lenses, it would form

a spreading beam, and an image of the lightbulb would be projected into

the distance. Laser light can form beams because a laser is a pointsource,

and when you project the image of a pointsource into the distance, you

form a narrow parallel beam! However, it is simply wrong to state that

laser light is inherently parallel light. Laser light can be

formed into parallel light, while the light from ordinary sources cannot.

Most types of lasers actually emit spreading, non-parallel light. Lasers

in CD players and in "laser pointers" are semiconductor diode lasers.

They create cone-shaped light beams, and if a parallel beam is desired,

they require a focusing lens. The same is true for the lasers in

inexpensive "laser pointers." Take apart an old laser-pointer, and you'll

find the plastic lens in front of the diode laser inside.

Classroom "HeNe" lasers also create spreading light. The laser tube

within a typical classroom laser contains at least one curved mirror

(called a "confocal" arrangement,) and it creates light in the form of a

spreading cone. It's a little-known fact that manufacturers of classroom

lasers traditionally place a convex lens on the end of their laser tubes

in order to shape the spreading light into a parallel beam. While it's

true that a narrow beam is convenient, I suspect that part of their reason

is to force the laser to fit our stereotype that all lasers produce thin,

narrow light beams. The manufacturers could save money by selling "real"

lensless laser tubes having spreading beams. But customers would

complain, wouldn't they? We have been brought up to believe that laser

light is parallel light.

CORRECTED: LASERS EMIT COHERENT LIGHT, BUT NOT

BECAUSE THE

ATOMS EMIT IN-PHASE LIGHT WAVES

In-phase emission causes the amplification of light, it doesn't

cause coherent light. Because the atoms emit light in phase with incoming

light, they will amplify the light, but they amplify incoherent light too,

and they don't make it coherent. The coherence of laser light has another

source...

Laser light has two main characteristics: it is "monochromatic" or very

pure in frequency (this also is called "temporally coherent.") Laser

light also has a point-source character of sphere waves and plane waves

(also called "spatially coherent.")

Even fairly advanced textbooks fail to give the real reason why laser

light is spatially coherent. They usually point out that the laser's

atoms all emit their light in phase, and pretend that this leads to

spatial coherence. Wrong. It is true that the fluorescing atoms in a

laser all emit light that's in-phase with the waves already traveling

between the mirrors. But the in-phase emission only creates

amplification of the traveling waves, it does not create spatially

coherent light. For example, if you were to feed incoherent light

into a HeNe laser tube, the atoms would emit in-phase waves, and the laser

would amplify the light. But the brighter light would still be

incoherent! Lasers certainly can amplify the coherent wave which

is trapped between their mirrors. But how did the light within the laser

get to be coherent in the first place?

Lasers create coherent light because of their mirrors.

The mirrors in a laser form a resonant cavity which preserves coherent

light while rejecting incoherent light. How does it work? Imagine a

simplified laser having flat, parallel mirrors. As light bounces between

the mirrors, the light "thinks" that it's traveling down an infinitely

long virtual tunnel. (Have you ever held up two mirrors facing each

other? Then you've seen this infinite tunnel.) When a laser is first

turned on, it fluoresces; it emits light which is not coherent.

Different random light waves start out from different parts of the laser.

After a few thousand mirror bounces, all the waves have added and

subtracted to form just one single EM wave. In the case of flat-mirror

lasers, this wave is a nearly perfect plane wave. A single plane wave is

coherent (to be incoherent, you must have at least two different

waves.)

This can be a bit confusing. After all, the individual atoms each emit a

wave. Don't all these waves add up to messy incoherent light? No. The

in-phase emission preserves the existing coherence as it amplifies. It's

true that each atom emits light waves in all directions. However, these

sideways waves from all the atoms will cancel each other out, and only the

waves that travel in the same direction as the incoming light will be

preserved. It's as if the atoms "know" which direction to send out their

beam. But in reality, the atoms don't need to know the beam direction.

Instead, they just emit a light wave which is in phase with the incoming

light, and for this reason the wave from the atom will cancel out

everywhere except in a line with the incoming light. If the light in a

laser were already coherent, then the atoms will amplify it but

won't make it more coherent. The coherence comes from the great distance

that the light has traveled as it bounced between the mirrors.

A similar thing happens with starlight: starlight is coherent! Starlight

travels far from its original source and all the waves from different

parts of the star will add up to form a wave with a single planar

wavefront. Light from distant stars is spatially coherent, even though

sunlight is not, yet the sun is a star too. The farther the light travels

from its source, the more it approaches the shape of a perfect plane wave.

And a perfect plane wave is perfectly coherent. Laser light is spatially

coherent because, among other things, the bouncing light has traveled

millions of miles between mirrors, and all the various competing waves

have melded together to form a single pure plane-wave or

sphere-wave.

P.S. The pure color (monochrome) laser light is also

created by the

mirrors. Huh? Yes, but the reason for this is not totally

straightforward (and it's quite a bit beyond the K-6 level of these

webpages!)

The two mirrors of a laser can trap a standing wave of light. The space

between the mirrors is like the string of a guitar: there can be a

fundamental wave, or overtone waves, or complicated waves which are a

mixture of these. But waves of non-overtone frequencies cannot exist

between the mirrors. Since the distance between the crests of a light

wave is very small, lots of different overtones can fit between the

mirrors, and each overtone is a slightly-different pure color of light.

Light from a neon sign is reddish, but it doesn't have the extreme purity

of laser light. Now for the weird part: when a Helium-Neon laser first

operates, many different overtones of red light are amplified and the beam

contains many slightly-different colors of red at the same time. It's not

yet monochromatic. As time goes on, some of these colors are amplified a

bit more than others, and this uses up the available energy coming from

the laser power supply. In other words, the different waves start

competing for limited resources! Just one wave "wins" in the end, and all

of the other overtones drop out of the running. The laser light is not

just red light. Instead it is a single pure overtone-wave, a pure

frequency where the string of waves just perfectly fits in the space

between the two mirrors. Change the spacing of the laser's mirrors (for

example by heating a glass HeNe laser tube,) and you change the frequency

of the light.

CORRECTED: IRON AND STEEL ARE NOT THE ONLY STRONGLY

MAGNETIC MATERIALS

There are numerous others. Nickel and

Cobalt

metals are very magnetic. (U.S. "nickel" coins contain copper which

spoils the effect, so try Canadian nickels made before 1985.) Most other

materials are "diamagnetic," and are repelled visibly by very strong

magnets, although some materials are "paramagnetic" and are attracted.

Supercold liquid oxygen is attracted by magnets. Some but not all types

of stainless steel are nonmagnetic. There are even some metals which are

individually nonmagnetic, but which become strongly magnetic when mixed

together, chromium and platinum for example, and compounds of manganese

and bismuth.

CORRECTED: RE-ENTERING SPACE CAPSULES ARE

NOT

HEATED BY AIR

FRICTION

They are heated as they plow into the atmosphere and

compress the air ahead of them. Ever pump up a bicycle tire and discover

that the pump and the tire have become hot? The same effect causes

spacecraft and supersonic aircraft to heat up as they compress the air at

their leading edges. The heat doesn't come from *rubbing* upon the air,

it comes from *squeezing* the air. This applies mostly to blunt objects

such as Apollo reentry vehicles. It does not apply as much to the Space

Shuttle: with wings oriented mostly edge-on to the moving air, the

surfaces of the Shuttle are heated by friction. But when the

Shuttle

first reenters the atmosphere, the bottom of the craft faces forwards,

and in that case the Shuttle is heated by air compression, not by

friction.

CORRECTED: CARS AND AIRPLANES ARE NOT SLOWED DOWN BY

AIR FRICTION

They are slowed because it takes energy to stir the air. While

direct

friction between the air and the car's surface does play a part, the work

done in stirring the air far exceeds the work done in direct frictional

heating. If vehicles did not send air swirls and vortices spinning off as

they moved, they would barely be slowed by the air at all. Eventually the

swirling air is slowed by friction and ends up warmer, but this occurs

long after the vehicle has passed.

CORRECTED: THE NORTH MAGNETIC POLE OF THE EARTH IS

NOT IN THE NORTH

Opposite poles attract. If we hold two bar magnets near each

other,

the "N" pole of one magnet is attracted by the "S" pole of another. If we

suspend a bar magnet by a thread, the "N" pole of that magnet will

point... toward the Earth's north!

Something is wrong here.

Shouldn't the

"N" pole of a magnet point towards the "S" of the Earth? Alike poles

should repel, not attract. Either the "N" and "S" printed on all bar

magnets is

reversed, or the "N" and "S" on the Earth is backwards. Which is

it?

This problem has a simple solution. Physicists define "N-type" magnetic

poles as being the north-pointing ends of compasses and magnets. This

definition is built into all of modern science and engineering and is part

of Maxwell's equations. Wind an electromagnet coil, see which end points

towards the Earth's North Pole, and that end is the "N pole" of the

electromagnet. And this means that the magnetic pole found deep inside

the northern hemisphere of the Earth is a south-type magnetic pole. The

Earth's northern magnetic pole is an S! It has to be this way, otherwise

it would not attract the N-pole of a compass.

This is a long-standing but arbitrary physical standard, much the same as

defining electrons as being negative. Like it or not, we are stuck with

negative electrons, with seconds which last about 1/100,000 of a day, with

backwards Earth poles, with centimeters which are about as wide as a small

finger, etc.

Interesting email

msgs on magnetic polarity

See Dexter Magnetics for more on this.

Also try this Google

search

CORRECTED: ACTUALLY THERE ARE NO SODIUM CHLORIDE MOLECULES IN SALT WATER

Salt is not made of NaCl molecules. Salt is made of a three-dimensional

checkerboard of oppositely charged atoms of sodium and chlorine. A salt

crystal is like a single gigantic molecule of ClNaClNaClNaClNaClNaClNa.

When salt dissolves, it turns into independent atoms. Salt water is not

full of "sodium chloride." Instead it is full of sodium and chlorine!

The atoms are not poisonous and reactive like sodium metal and chlorine

gas because they are electrically charged atoms called "ions." The sodium

atoms are missing their outer electron. Because of this, the remaining

electrons behave as a filled electron shell, so they cannot easily react

and form chemical bonds with other atoms except by electrical attraction.

The chlorine has one extra electron and its outer electron shell is

complete, so like sodium it too cannot bond with other atoms. These

oppositely charged

atoms can attract each other and form a salt crystal, but when that

crystal dissolves in water, the electrified atoms are pulled away from

each other as the water molecules surround them, and they float through

the water separately.

CORRECTED: LIGHT AND RADIO WAVES DO NOT ALWAYS TRAVEL AT "THE

SPEED OF LIGHT"

They only travel at the "speed of light" (186,000 miles per second) while

moving through a perfect vacuum. Light waves travel a bit slower in the

air, and they travel lots slower when moving through glass. Why

does

light bend when it enters glass at an angle? Because the waves SLOW DOWN.

Why can a prism split white light into a spectrum? Because within the

glass the different wavelengths of light waves have different

speeds

And while the numerical value for the speed of light in a vacuum, "c," is

very important in all facets of physics, as far as light waves are

concerned there is no single unique speed called "The Speed Of Light."

[note for advanced students: ok ok, I'll add this: light *waves* within a

transparent medium are slow, even though the wave's photons are thought to

jump from atom to atom always at a speed of c. But such ideas are not

very honest, since whenever we only pay attention to the vacuum between

particles in a solid, we stop treating the solid as a "uniform transparent

medium." ]